QI Essentials: Improvement as a specialism

13th February 2020

Quality improvement has come of age.

It’s wonderful to see the increasing belief in the systematic approach of quality improvement, within the NHS and also further afield. The evidence base is growing that we can solve our most complex issues in health and healthcare by deeply involving those closest to the issue in a process of discovery and learning.

For those of us who are practicing and studying the science and art of improvement, this brings great opportunity – to shepherd and guide large scale improvement, to help nurture cultures of continuous improvement, to develop career pathways for those who wish to develop expertise in quality improvement.

I’ve been thinking recently about what we, as a community of improvers, can do to strengthen improvement as a specialism. A specialism is an activity or study that one becomes expert in and devotes oneself to. How can we strengthen the expertise and aggregation of learning within the field of quality improvement, but without making it exclusive? Ultimately, if our goal is to develop cultures of continuous improvement, we need to democratise improvement and enable everyone to believe they can improve the system, and have the knowledge and skills to do so. So, how best to do this whilst also developing expertise and rigour in the application and discipline of quality improvement? Here are two areas where I feel we can make collective impact…

There’s been a proliferation in recent years of the use of the words ‘quality improvement’. I see job descriptions now with the title including the words ‘quality improvement’, and often wonder whether the job is actually different, or whether the title has just changed? More and more organisations seem to be developing quality improvement teams and plans. I wonder how much is really based on belief in the method, and how much is simply because we feel we have to follow this path? Many of those charged with leading quality improvement within organisations feel disconnected from leadership and strategy, and quality improvement can so easily be viewed and set up as an end in itself, rather than be the way that we deliver our organisational plans and achieve our collective goals. Alongside the proliferation of QI in job titles, I see and hear people talking about improvement collaboratives, often without any obvious resemblance to the principles of good improvement design. Any programme of work these days seems to be able to be labelled an ‘improvement collaborative’. I’m not sure what the theory is behind this – do people feel that it will engage others better? Does it seem like a more attractive way of framing our work? Surely we’re all trying to improve things, so what harm can it do?

I’m sure all of this is done with the very best of intent, with the aspiration to help us improve. However, if we, as committed scholar-practitioners of improvement, don’t call out the inappropriate use of the words and language of quality improvement, we risk undermining the rigour and specialism. Pretty soon, we can expect people to start stating that ‘quality improvement doesn’t work’. But is it really quality improvement that doesn’t work, or the way in which we are executing it? Quality improvement gets diluted to an aspiration, rather than a discipline. We need to help people understand how to apply quality improvement properly, using the discipline and scientific thinking, and integrating it into the way we work rather than becoming a shiny standalone programme.

When I look to the literature to learn from examples of excellent quality improvement work, there’s far less than we ought to find. A tiny proportion compared to the research literature. So the second way that we as improvers can build our field into a genuine specialism, is to share our learning and outcomes. We need to describe the robust methods and design that we use, and help others recognise the principles of good improvement when they see it. We need to celebrate the learning and results we generate, so that we can continue to help build belief that quality improvement, when applied properly, can genuinely achieve transformational change. But only when applied properly, with skillful guidance and rigour.

If this call for improvement to become a specialism has resonated with you, then join me… I’d love to hear from you.

Most Read Stories

-

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

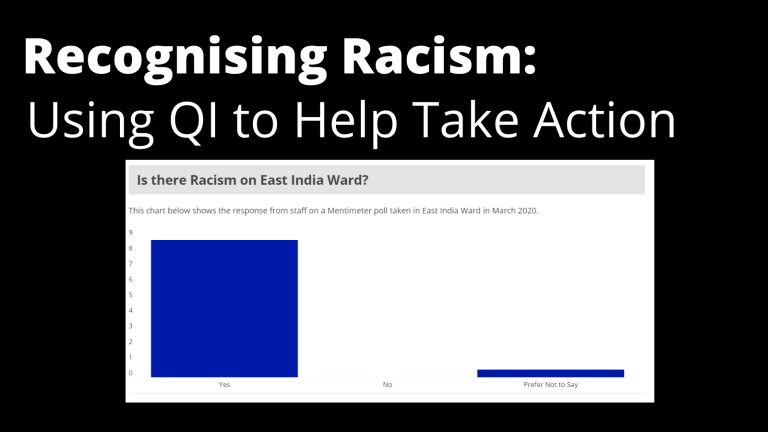

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.