Reducing violence and improving quality: ELFT’s journey

28th August 2018

In this blog, Andy Cruickshank, ELFT Interim Director of Nursing for Mental Health, describes the journey from the Violence Reduction priority area to the Time to Think initiative.

The decision to use quality improvement methods to reduce violence was one that has reaped so many unexpected benefits. At first, the testing on Globe Ward in Tower Hamlets didn’t really show any significant improvement – it wasn’t until the wisdom in the team became central to the improvement that there was a shift in the data. And then, as the ideas grew, it was clear that other forms of measurement were needed to determine how the change ideas were affecting practice and the climate of care on the wards across Tower Hamlets. We had hoped for modest improvement but the results were more substantial – so much so that it felt as if something had really fundamentally shifted in our perceptions of what could be done to prevent conflict.

In QI parlance, scaling up of an intervention is one of the hardest things to achieve. It is easier to manage, contain and direct changes at a smaller scale of 1 service user, 1 member of staff or 1 team. Being able to sequentially test ideas over several teams and sites and gather the data, make sense of it and develop reliable processes that staff and service users can believe in is a much more exacting task. However, we decided to try and accelerate our learning about what works by using an approach called planned experimentation. This is a way of testing multiple ideas to gauge the most effective combinations – so that we only focus our efforts on the most crucial things and not on those that effect things peripherally or not at all. When there are several changes occurring in one setting it is hard to separate the relative effects of each or determine whether there is an ideal sequence to follow. The inpatient teams in Newham and Hackney were up for the challenge and were soon into learning together about what works with some fantastic results.

In all of this, one factor has been so important yet, really didn’t become apparent until a bit later in our learning. The idea that people – staff and service users – can come together and talk openly and honestly about what was happening was for me the single most important aspect of this endeavour. Something about the courage and willingness to do this really did begin to change what wards felt like. The lived reality of our hospitals is that they are full of opportunities to create conflict through the imposition of rules and treatment – learning to listen and think together can soften the language, develop warmth, empathy and understanding. It is no coincidence that the teams that showed the greatest improvements tended to demonstrate this reliably.

Given the reductions we saw in violence, we expected a more uniform reduction in the use of restraint and seclusion and the use of rapid tranquillisation. But this was not the case. What the data told us was that some wards did see quite stark reductions but others, in particular our intensive care units – did not. Targeting this is a priority now. Restrictive practice is driven by a combination of necessary restriction for safety as well as perceptions and behavioural norms in teams.

Simply speaking, we use it as an approach because it is seen to be effective in gaining control and retaining it – sometimes in frightening situations this is absolutely required but we also know that some careful thought and planning can prevent a great many instances of restraint and seclusion. As mundane as it might sound, simply developing conversations with teams and service users about this is the foundation of improvement. So this phase of our work is about sustaining the gains of the original improvement work and the use of the bundle of tools to guide safety and also developing new ideas about changing the way that we work in order to reduce the amount of restrictive practice we use. It is not easy but that is why we are running Time to Think Meetings. If we ask ourselves to stop and think – we naturally need a space and a time to talk about our thinking and what we have been trying out. Please join this discussion and be part of a movement to rethink the way we provide care.

A young staff nurse asked me the other day; “In 50 years’ time, will people look back on our care and treatment and think: “How could they have treated people in this way?”

Our challenge is about how we can shape care for not just this but future generations – the change starts with us.

Most Read Stories

-

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

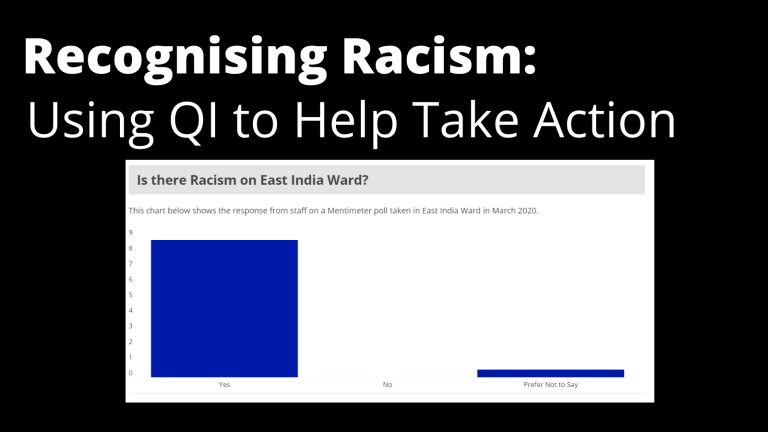

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.