Forensics: an honest conversation about failure and what we’ve learnt as a directorate

23rd November 2017

The Forensic Service has an active and diverse QI Programme, which has enjoyed many notable successes. Some projects don’t succeed though. We recently spent some time thinking about the learning we could take from those, and how to keep enthusiasm and momentum within the group of people who have invested their time and energy.

Learn more about overcoming obstacles in this blog written by the Forensics QI Sponsors, QI Coaches and Improvement Advisor.

“Project team disengaged”

“Project has lost momentum”

These are the two most common forms of feedback we hear during the Projects’ Progress Update in the Forensics monthly QI Business Meeting and Breakfast QI Forum. At least half of the projects in the Directorate’s portfolio are in a similar state, month-on-month. Undoubtedly, it is frustrating to see a once great idea and an enthused project team with a promising improvement project grinding to a halt. It is not the outcome that had been envisioned, especially after witnessing how some excellent QI projects have flourished, and bought about significant improvements to our service such as the Self-Catering by Service-Users and The Bridge Club to name a few.

We have plenty of goodwill as the local QI team (QI Sponsors, QI Coaches and Improvement Advisor) to help re-energise these inactive projects. Unfortunately, the actual uptake of this help by project teams has been low. As a result, we felt stuck with forging ahead constructively to help restart these inactive projects. An instinctive outcome would be to instruct closure but instead, we saw this as an opportunity for us, as the local QI team to better understand what was failing these project teams, and share some honest reflections on project viability and their importance.

Our analysis started with an honest conversation on ‘why do viable QI projects struggle or become a non-starter?’ We structured our reflection and thinking by using the Cause and Effect Diagram. What was immediately evident was that current culture of the workplace interconnected with many other causes identified. For example, ‘lack of personal sense of agency’, ‘no shared belief’, ‘doing QI is not part of job plan, it is outside of staff’s day-to-day work’, and ‘QI is held by the project team ’. Therefore, culture is one of the biggest barriers towards the chances of a project succeeding.

On the other hand, the leading enabling force for carrying out a QI project is ‘reliance on goodwill’ and special interest of the Forensic Staff. It was clear to us that the starting point and change formula would be to effectively manage and support the goodwill and passion from staff to lead on change, and foster a shared vision that all staff have a role to play in QI to deliver continuous improvements for the directorate.

We had a timely visit from the Institute for Healthcare Improvements (IHI) to Forensics, where we had the pleasure of obtaining guidance from Executive Director Pedro Delgado. He suggested we could champion the importance of all QI projects to the service as this can help to create the shared vision cascading down to the front line staff. Also, “Where we succeed, we celebrate. Where it doesn’t work, we learn”. We need to be open and transparent with unsuccessful projects. There is valuable new knowledge in each of them that we can all learn from. We should also take time to thank our project team for their time and energy for running a QI project even if it was an unsuccessful attempt.

Since the discussion with Pedro, we have taken on these valuable lessons to refine our processes for project closure. We have refined the forums on how we can share the learnings from unsuccessful projects. Systems have also been developed to manage the closure process to ensure project teams are recognised for their efforts and contributions to continuous improvements for the service. We will certainly be running our Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles to ensure the processes are building into the culture.

It took Thomas A. Edison 1000 attempts to create the lightbulb but he recognised that he had not failed but just found 1000 ways that don’t work. We feel that we are on a similar journey of discovery. We have not failed, but we have certainly learnt what structures and processes are needed in order for QI to be sustainable in Forensics in the long run. We were able to persevere and do so because we stayed connected to our core intention that is we truly believe in our staff, their QI projects, and the benefits it can bring to the service and our service users. As Dr Paul Gilluley summarised in his tweet:

“@NHS_ELFT sometimes you need to look back and recognise how far you have come before you look up push on with the climb #forensic #QI”

This is the start of our climb, and we look forward to the coming months learning as a service how best to deliver, enable, and better support staff in doing QI.

Read some of our QI Sponsors and QI Coaches personal reflections on what helped them to stay connected:

“QI could have been another failed NHS change that would soon fizzle out with time. It takes time to grow on you, once bought into the idea and seen the scope for continuous change and challenging the norm (this is how we do things here), you realise that the gift is in our hands to improve the quality of service for staff and patients. I am particularly pleased by the adoption of QI as a way of working rather than an added extra to the role. The changes have been slow, at times painful, disheartening, tiring and you realise early on that this is a long haul flight.” – Day Njovana, QI Sponsor for Forensics

“I’m all for change and improvement, that’s why I got into coaching. It’s not a good feeling when projects don’t go as far as you envision. In the beginning you get a feel of a project and can project a potential outcome, especially when there are people who are invested. So to see a project halt or teams become disengaged, is not an expected outcome. I don’t like to give up. I look at the reasons behind why a project or idea was suggested in the first place and see whether it could have brought about a change. This is a driving factor for me wanting to continue and forging on. My hope and vision is to see the project do what it was created to do and hopefully more.” – Kimalee Foster, QI Coach for Forensics

“I felt very frustrated for the team that the project was not starting up. I wanted the team to feel the benefits of starting something worthwhile, a project that hopefully would improve their working days and their customers’ experiences. I didn’t want to give up on them or the project. Previously there hadn’t been clear and coherent acknowledgment on the part of the service of this project’s importance, now there was. This helped the team to really believe that their project was worthwhile on a wider scale than they’d maybe realised before. They now began and quickly the project came to life. On reflection, this has been the case with many of the successful projects, and I now realise a key factor to look out for in a project’s early days is the explicit support of the service the project takes place in.” – Charles Kennedy-Scott, QI Coach for Forensics

Most Read Stories

-

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

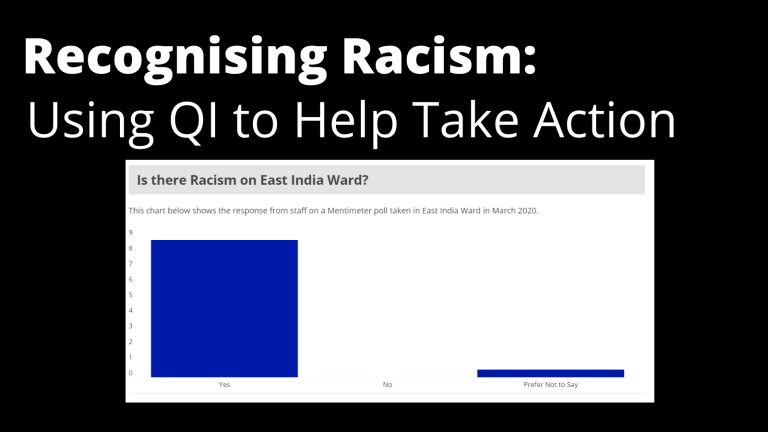

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.