QI Essentials: The daily practice of improvement

26th April 2019

What does it take to make quality improvement a part of our every day habits and behaviours? Have a read of Amar’s latest QI Essentials blog…

In “Outliers – the story of success”, Malcolm Gladwell challenges the notion that success is based on innate skill, hard work or focused ambition. Or that we can ascribe the success of an individual purely down to factors related to that individual. Gladwell writes about the role of family, culture and friendship in an individual’s success, stating that “what we do as a community, as a society, for each other, matters as much as what we do for ourselves.” In studying the success of individuals across a range of disciplines, Gladwell suggests that 10,000 hours of practice are needed in order to develop world-class expertise in a particular skill, since dubbed the” 10,000-hour rule”.

Quality improvement is definitely a skill that needs to be practised in order to refine and improve one’s technique, much like my piano playing. QI isn’t simply knowledge, or a method. We know from many evaluations and studies that most people and organisations, despite knowing the theory of quality improvement, struggle to actually apply it on a consistent and regular basis in daily work. And what does it really mean, to make quality improvement part of everyday work? I hear frequently the phrase “making quality improvement business as usual”, but what does this actually mean?

For many organisations, quality improvement consists of structured projects aimed to specific improvement opportunities with multidisciplinary teams coming together to work on a goal of shared interest, using improvement tools and a systematic method. But does a programme of multiple projects equate to making quality improvement part of daily work? Organisations that have truly embraced a continuous improvement philosophy and demonstrated fidelity to this for a decade or more have found that it involves more than just projects. Of course, that’s not to say that projects aren’t important. QI projects are an absolutely vital mechanism for delivering tangible improvement on specific complex issues, bringing together a group of stakeholders to discover solutions and test them out over a period of several months. The accumulation of projects across the breadth of an organisation and over time helps transform organisational performance to new levels.

However, the downside of viewing the adoption of continuous improvement in an organisation as simply a programme with multiple projects is the risk that quality improvement becomes limited to only being practised within projects and by the small groups of people coming together around projects. The true opportunity of quality improvement lies in both tackling strategic improvement opportunities through robust project structure AND using our quality improvement skills on a daily basis to help us identify challenges and improve processes every single day, by every single person.

So, what does it take to be able to move beyond training people in QI skills and deploying these to QI projects, to using quality improvement in our every day work, no matter what our role? And will simply practising be enough to become world-class in quality improvement? Certainly, we’ve seen in our work at East London NHS Foundation Trust that it’s important to be able to try out the skills of improvement, see the effects, learn about the method through actually trying it out on real-life improvement opportunities – and that this helps build not only confidence in the approach, but also the skill in being able to use it effectively. Some of the recent evaluations of the use of Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles by Julie Reed and colleagues at North West London CLAHRC are highlighting the importance of properly learning and applying the method, practising in the real-world with skilled support to guide. So, could we consider that deliberate practise will help us become great improvers and how many of us could realistically hope to achieve this, given that it would need 20 hours of practise a week for 10 years in order to achieve Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule?

Well, firstly, there’s increasing evidence that deliberate practise by itself may not be as important as we originally thought in improving performance within a particular domain. A meta-analysis from Princeton University in 2014 looking at practise and performance across domains such as music, sports and games have found that practice explained 26% of the variance in performance for games, 21% for music and 18% for sports, but only explained 4% of the variance in performance in education and less than 1% for professions. The theory is that deliberate practice is only a predictor of success in fields that have very stable structures. For example, in chess, tennis and classical music, the rules never change – so studying more and practicing more has a much greater effect on performance. I’d argue that the world of healthcare is much less stable – our systems our complex and ever-evolving, the use of improvement needs to be highly adaptable and dynamic. So although deliberate practise is likely to be important in becoming proficient in using quality improvement skills, it’s not going to be enough for us to become truly world-class improvers.

So, if practise isn’t enough, what else does it take? Perhaps the place where I’ve found most learning about this is from Mike Rother’s six years of research in Toyota and their management thinking and practice, that have enabled it to embed continuous improvement and adaptation into and across the organization in a way that few other organisations have been able.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising to some, but the key is… behaviour. Specific behaviours, habits and patterns of thinking and conducting oneself, that are practiced over and over, every day at Toyota. In Japan, these routine habits and behaviours are called kata. It’s a way of practising scientific thinking – moving towards a mindset of seeing our environment and work as a system, identifying opportunities, developing theories, and seeing the value of testing, learning and adapting. Avoiding jumping to conclusions, but practicing a systematic approach to understanding the world around us, comparing what we think (our theory) with what we see (evidence) and adjusting based on the difference between these two.

Kata is applicable to all, including leaders – perhaps particularly for leaders, where it is easy to feel the need and pressure to find solutions to challenges, and to believe that we have the best solutions by virtue of our expertise, experience or skill. At Toyota there are two types of kata that are key: the improvement kata, and the coaching kata. The improvement kata describes a systematic approach to being curious about the status quo, seeing the work around us as a system, bringing people together and opening our minds to different theories that would improve the system, testing these and adapting based on what we see. The coaching kata is key to the role of managers and leaders, in teaching the improvement kata and bringing it into the organization. The primary role of Toyota’s managers and leaders is about increasing the improvement capability of people, developing people who in turn improve processes and systems through the improvement kata. This involves a set of practices which have their roots in the Buddhist master/apprentice teaching method – guiding, teaching, encouraging, showing, developing, enabling the person to discover things for themselves through using the improvement kata.

In our learning at ELFT about embedding quality improvement into daily work, it’s clear that QI projects and training are absolutely key – to help us learn and practise the skills, build belief, create step-changes in performance on complex quality and safety issues. But we’ve also learnt that the real value comes in applying what we’ve learnt into our daily habits and rituals as ‘improvement kata’ – bringing our scientific thinking into the way we understand our work and challenges on a daily basis, using our simple QI tools where and when they make sense, involving people in a more meaningful way in developing theories, using the discipline of test-learn-adapt to continually improve ourselves and the world around us. And the role of leaders and managers is key to this – in inviting ideas from a diverse range of people, in stopping us from jumping to conclusions, in encouraging the testing of creative ideas, in helping us find time to think together…

You can read all past QI Essentials posts here.

Most Read Stories

-

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

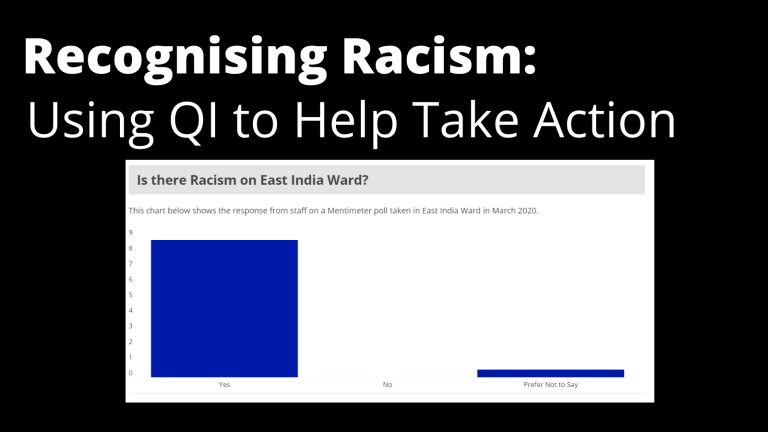

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.