Empowering Health Equity: A Quality Improvement Journey on a Male PICU Ward

8th November 2024

Authors: Satwinder Kaur (QI Coach with Lived Experience) and Chloe Preston (Improvement Advisor)

Jade Ward, a male psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU) in Luton, Bedfordshire, aimed to address the physical health disparities faced by people with severe mental illness by focusing on physical health, fitness, and culturally relevant care.

Figure 1: Jade ward in Luton, Bedfordshire

What did the team want to accomplish?

People with severe mental illness (SMI) face life expectancies averaging 15 to 20 years shorter than the general population, this disparity is largely due to preventable physical illnesses (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2023). This QI project aimed to address this major health disparity by focusing on physical health, fitness, and healthy eating on Jade ward, a nine-bed, male psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU) in Luton. Specifically, the project looked to address ethnic inequalities linked to physical health, in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on Body Mass Index (BMI). Considering this intersectionality ensured that any changes were culturally relevant and equitable, fostering personalised care that can improve patient satisfaction and engagement.

The project’s SMART aim: Increase the average score of patient satisfaction regarding the consideration of their ethnic background in the assessment and management of their physical health by 10% by October 2024

The project had both Big I and little i service user involvement. The team consisted of ward staff and two members with lived experience of inpatient services: Steve and Jake. Steve was keen to share the mental health benefits of physical activity, while Jake championed healthier eating options, advocating for greater vegan options on the ward. The team also regularly sought ideas and feedback from service users on the ward, ensuring authentic involvement in the work.

What changes did they develop and test?

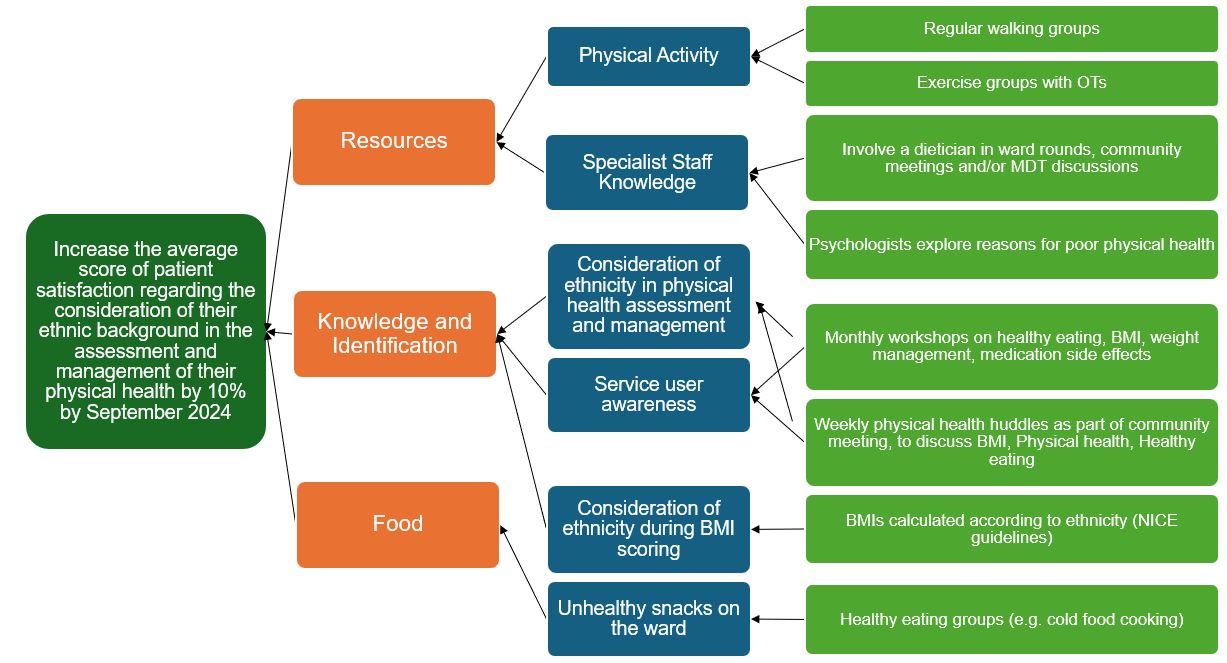

See the team’s theory of change, presented as a driver diagram, in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: The project’s driver diagram. Left to right: aim, primary drivers, secondary drivers, change ideas.

The team have gone on to implement three successful change ideas, using Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles to develop and test them. See these below, along with learning for each idea.

Physical Health Huddles

The team first tested physical health conversations as part of the weekly community meeting, before testing and implementing a distinct weekly healthy lifestyle huddle.

Learning:

- Physical health conversations are easy to introduce into the existing weekly community meeting. A specific weekly huddle should be held separately and involve a Doctor, Nurse or other Advanced Clinical Practitioner, as having protected time was more effective at engaging service users.

- Using ‘What matters to you?’ framework is effective in beginning conversations.

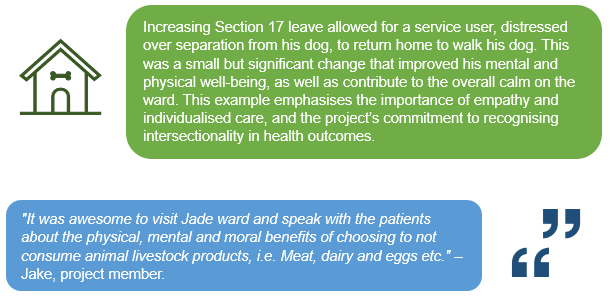

Increased Section 17 Leave

The team implemented increased Section 17 leave to allow service users to take part in physical activity off the ward, for example walking groups.

Learning:

- Service users enjoy being out of the ward and being active.

- Section 17 leave needs to be carefully planned around staffing levels and observation levels.

- A ward round and a service user discussion should be utilised to grant the leave.

- This change idea can be seen as a ‘win-win’: both staff and service users have the opportunity to exercise, and it was found to be a positive way for staff to interact with service users.

Physical Health Passports

The team developed a portable record for service users to complete, based on the ‘What matters to you?’ framework, encompassing key factors like family history, ethnicity, hobbies, and individual health priorities, designed to empower patients in managing their health across different care settings.

Learning:

- PDSA cycles should be used to iteratively develop the passport, based on feedback from service users and staff.

- Content should be holistic, not be too medical and not contain any confusing jargon or abbreviations.

It is most worthwhile for the service user to complete digitally. It can then be updated when desired, printed off when service users are discharged from the ward, and uploaded to RiO to be available for continuing care on open wards and in the community.

What were the outcomes of the project?

The results of these changes were captured throughout the project, both qualitatively and quantitatively, using a service-user survey and collecting ongoing verbal feedback. Service users and staff reported enhanced communication, with patients feeling more empowered to engage in physical activities. Both staff and service users gained new knowledge on healthier lifestyles, and staff appreciated the opportunity to build rapport with patients in a relaxed, outdoor setting. The survey also gave service users the opportunity to identify what matters to them with respect to their physical health, allowing continuous learning for the team (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A word cloud representing responses from service users when asked the question: ‘What matters to you considering your physical health, family history and ethnicity? What other interventions or other options would you like available to you?’

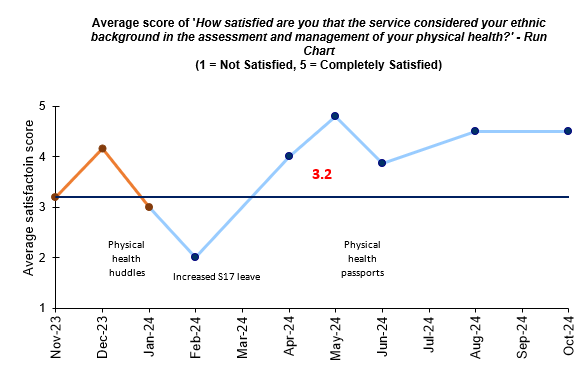

The survey also captured service user satisfaction over time, displayed on a run chart below (Figure. 4).

Figure 4: A run chart showing the average satisfaction that the service considered service user’s ethnic background in the assessment and management of their physical health. Orange points represent baseline.

The project not only improved awareness and understanding of physical health, but also raised awareness about ethnic inequalities in obesity rates, following NICE guidelines to promote better, fairer health outcomes. The Jade Ward team’s success demonstrated the power of patient-driven, equity-focused QI work in creating sustainable changes in healthcare.

References

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. (2023) Severe mental illness and physical health inequalities: briefing. GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/severe-mental-illness-smi-physical-health-inequalities/severe-mental-illness-and-physical-health-inequalities-briefing (Accessed: 29 October 2024).

Most Read Stories

-

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.