Most Read Stories

-

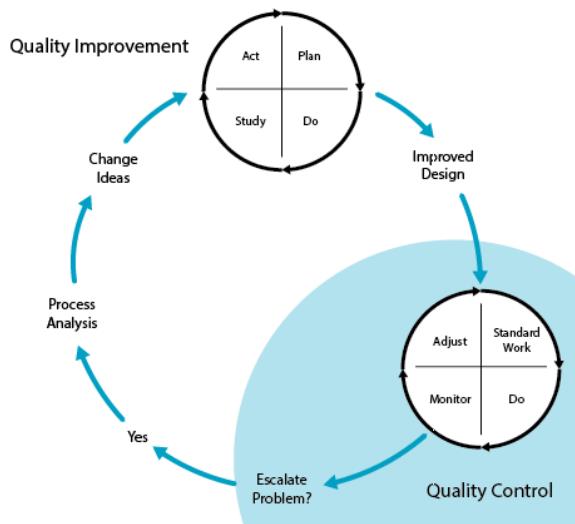

Why is Quality Control important?

18th July 2018

-

An Illustrated Guide to Quality Improvement

20th May 2019

-

2016 QI Conference Poster Presentations

22nd March 2016

-

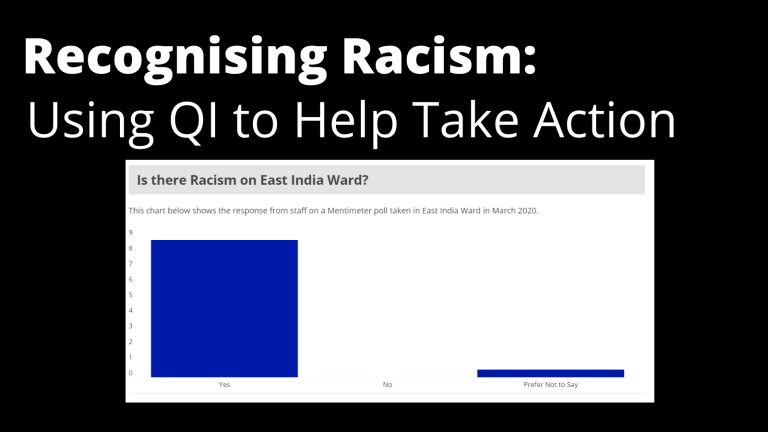

Recognising Racism: Using QI to Help Take Action

21st January 2021

-

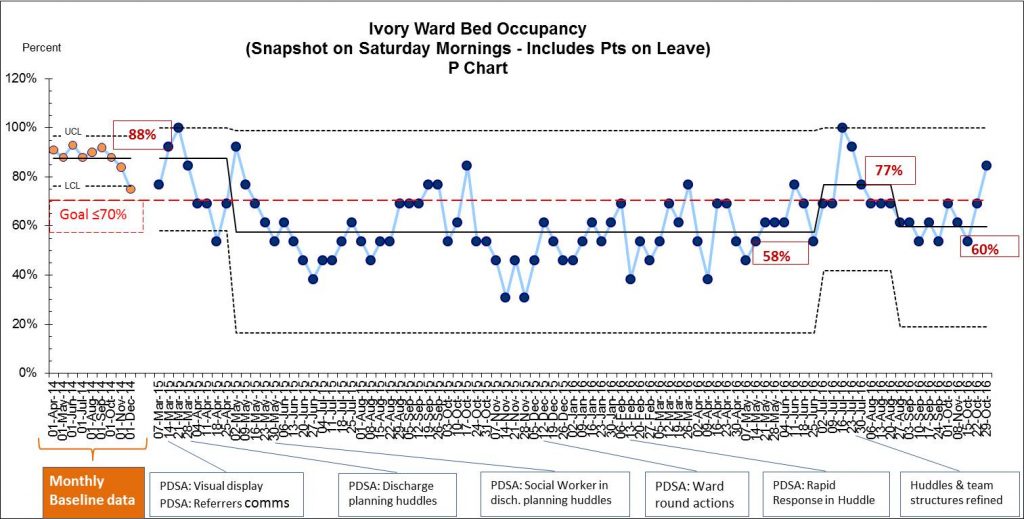

Using data enabled us to understand our problem

31st March 2023

-

QI Essentials: What does a Chief Quality Officer do?

18th March 2019

Follow QI on social media

To keep up to date on the latest concerning QI at ELFT, follow us on our socials.